RESEARCH ARTICLE

- Emmanuel Ejembi Anyebe 1

1Department of Nursing Sciences, College of Health Sciences University of Ilorin, Nigeria

2Faculty of Nursing Sciences, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author: Emmanuel Ejembi Anyebe, PhD, RN, FWAPCNM, Mental Health Nursing Unit, Department of Nursing Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria.

Citation: Emmanuel Ejembi Anyebe, Mental Health Status and Mental Health Self-care Practices of Nurses in a South-west State in Nigeria: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study, Mental Health and Psychological Wellness, vol 1(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.64347/3066-3032/MHPW.001

Copyright: © 2024, Emmanuel Ejembi Anyebe, this is an open-access article distributed under the terms of The Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: March 16, 2024 | Accepted: April 20, 2024 | Published: May 20, 2024

Abstract

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021), self-care refers to all actions that individuals, families, and communities engage in to improve their health, avoid disease, reduce illness, and restore health. Self-care is a deliberate self-care plan, involving self-management, self-compassion, self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-monitoring. Thus, it consists of both self- regulatory activating and inhibiting practices (often referred to as stress-relieving hobbies), including chat box, exercising, journaling, eating healthy, meditating, maintaining outside interests, friend-building, and praying, among others (Moilanen, et al., 2023; Purdue University Global, 2023; Tachias and Ferguson, 2019; Peprah, et al., 2019).

Keywords: Mental Health, Self-care, Nurses.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021), self-care refers to all actions that individuals, families, and communities engage in to improve their health, avoid disease, reduce illness, and restore health. Self-care is a deliberate self-care plan, involving self-management, self-compassion, self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-monitoring. Thus, it consists of both self- regulatory activating and inhibiting practices (often referred to as stress-relieving hobbies), including chat box, exercising, journaling, eating healthy, meditating, maintaining outside interests, friend-building, and praying, among others (Moilanen, et al., 2023; Purdue University Global, 2023; Tachias and Ferguson, 2019;Peprah, et al., 2019).

Self-care is a standard of care, recommended for all nurses (American Nurses Association, ANA, 2015), regardless of whether the individual is a nursing student, a fresh nurse graduate, an acute care nurse, or a community health nurse or even setting (Chipu & Downing, 2020). Prioritising self-care is thus a professional and an ethical responsibility for all cadres of nurses, as well as a prerequisite for quality care and better patient outcomes (Mills, et al., 2015). Identified areas of self-care include physical, spiritual needs, positive (social) relationships, personal, professional, and medical aspects, school-work-life balance, as well as mental health and emotional wellness (Butler, et al., 2019; Jannie, 2021). They are the promotive and preventive mental health activities nurses need to engage in.Promotive and preventive interventions which focus on reducing risk factors and enhancing protective factors associated with mental ill-health are paramount for individuals to be aware of. Nurses as individuals healthcare professionals are also influenced by many economic, social, political, institutional, professional and personal factors of (mental health) self-care (Akinwale & George, 2020; Wolter, 2020; Zing, et al., 2020). Among other health professionals unlike for nurses, mental health self-care has attracted huge empirical attention. For example, among dental practitioners, concern were raised and and measures put in place to ensure delivery of quality mental health care (Barnard, et al., 2020). Many nurses, on the other hand, have reportedly regarded self-care as a luxury, and have overlooked it, focusing almost solely on patient care as their only top priority (Sist, et al., 2022). This is in spite of evidences showing that most nurses (between 60 and 80 percent express concerns about their physical and mental well-being being harmed, due to stressful life and work conditions (O’Malley, et al., 2022; Llop-Gironés, et al., 2021). As front-line healthcare workers, nurses are constantly being exposed to care situations that significantly affect their mental health, often manifesting as anxiety, insomnia, compassion overload and distress, depression, among others. Nurses as caregivers are two times more mentally distressed higher when compared to general populations (Bui, et al., 2023).

Recently, Delgado, et al., (2022) in their qualitative study of mental health nurses’ resilience recommended the need for nurses to build resilience, by being attuned to self and others, having a positive mindset grounded in purpose, maintaining psychological equilibrium through proactive self-care. they also reported how nurses impede their resilience by emotional draining. Other measures recommended for nurses include internal self-regulatory processes to manage their mental and emotional state, maintaining intra- and inter-personal boundaries, and proactively using self-care strategies to maintain their well-being (Delgado, et al., 2022).

However, at both personal and institutional levels, mental healthcare including self-care, is often neglected despite increasing burden of mental health problems (O’Malley, et al., 2022; Richards,et al., 2018). Primary (promotive and preventive) mental healthcare services where this care can be enhanced have remained conspicuously absent in many sub-Saharan Africa countries (Anyebe, et al., 2020; Anyebe, et al., 2019). Creating the individual, social and environmental conditions to facilitate optimal mental health promotion, especially for those at increased risk like nurses who constantly have to accommodate stresses of caring, remains challenging (Hosman & Jané-Llopis, 2015;Austen, 2015).

In Nigeria and elsewhere, the health systems expose healthcare professionals including nurses to very harsh working conditions (Morgan, 2022; Llop-Gironés, et al., 2021; Akinwale & George, 2020; Murray & Lopez, 2015), and measures to encourage self-care practices among nurses have become very crucial. Though self-care by nurses is generally low, the mental and emotional components are the most neglected (Anyebe, et al., 2022). An investigation into self-care, focusing on mental health, using the WHO guidelines has become imperative as the there is no health without mental health (WHO, 2021). This study examined the mental health status and mental health self-care practices among nurses in Ekiti State, southwest Nigeria. For this study, mental health status is the present state of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional well-being of individual nurses, while mental health self-care includes all self-reported actions of the nurses to enhance their capacity to promote their mental health, prevent mental illness, and manage mental health problems if present.

Methodology

Research Design: A descriptive cross-sectional design was used in this study to assess the mental health status and promotive mental healthcare practice among nurses in Ekiti State.

Research Setting and Target Population: This research was carried out among nurses at three tertiary health facilities in Ekiti State: three university teaching hospitals (Facility A – a state-owned hospital; Facility B – a private tertiary facility; and Facility C – a federal facility).

Study population: The entire nurses working in these three facilities constitute the target population for the study. At the time of this study (March-April, 2021), there were 327 nurses in Facility A, 356 nurses in Facility B, and 90 nurses in Facility C, making a total of 773 nurses.

Sample size determination and Sampling

Sample Size: There is total number of 773 male and female nurses working in the three teaching hospitals available for this study. A sample size calculation was made based on Taro Yamane’s (Rafael, 2014).) formula for calculating sample size. Taro Yamane method: n= N/(1+N(e)2): n= 263

Sampling: A purposive sampling technique was used to select the three teaching hospitals (a private facility; a State Government hospital; and a Federal Government institution) for this research study. A stratified proportionate sampling technique was to select nurses from each of the three hospitals. The study participants were selected through an availability-convenience sampling technique.

Instrument for Data Collection: A questionnaire with a section on Personal Data Information and another section adapted from General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) (Kashyap & Singh, 2017), tagged “Mental Health Promotion and Mental Health Self-care Questionnaire (MHPSCQ)" was used to collect data from the study participants. Designed in English language, the questionnaire comprised four sections: A, B, C and D.

Section A: Socio-demographic characteristics = 8 questions;

Section B: Assessment of Mental Health Status = 12 questions;

Section C: Attitude of nurses towards promotive mental health care = 8 questions;

Section D: Practice of promotive mental health care = 5 questions.

The instrument was assessed by four mental health experts for content and face correctness and pre-tested among 20 nurses in a General Hospital in Ado Ekiti. Its reliability (using Cronbach alpha) was 0.91.

Method of Data Collection: With a letter of introduction (Reference number: 21/03/230) from the Research and Ethics Committee, approval for this study was obtained (with Protocol numbers /2021/05/30/550B and 67/2021/05/07). Working relationships were established with all the facilities. Informed consent form was developed by the researchers and signed by the participants. Anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents were respected; all respondents participated voluntarily. All other ethical responsibilities were adhered to for the protection of the study participants. The questionnaire was administered to the respondents at their work stations, by two of the researchers and two other research assistants trained for the study. The questionnaires were retrieved immediately, resulting in 100% response rate. The response rate was possible because of the personal contact approach used.

Data Analysis: Data were cleaned and checked for errors. Out of the 263 questionnaires retrieved, three were not analyzable; the remaining 260 questionnaires were then coded and entered in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25.0. The internal consistency reliability estimates were then established. Descriptive statistics was computed for all variables and presented using tables and charts. For the first hypothesis, a bivariate analysis (chi-square test at 0.05 level of significance) was used to assess the association between socio-demographic variables and practice of promotive mental health care, and to test the relationship between nurses’ years of experience and their practice of promotive mental health care. Afterwards, a multivariate logistic regression was used to measure confounders.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the Study Participants

The nurses age distribution shows a mean of 28 years (SD±6.92 years), with most of them being females (81.9%), married (77.7%), Christians (94.6%) and of the Yoruba ethnic extraction (n=225; 86.5%). On their professional/educational preparation, those with only Registered Nurse (RN) certificates were the majority (67.7%; n=176) while only 15% (n=39) was Registered Mental Health/Psychiatric nurses (RMHPNs), with a few with first degree in Nursing. They were predominantly junior cadre nurses (from Nursing Officers, NOs. to Principal Nursing Officer, PNOs) (n=246; 94.6%), in the early years of their career (within the first 10 years of working experience: 74.6%; n=194).

Mental Health Status of Nurses in Ekiti state

Table 1 indicates results of the nurses’ self-reports on their mental health status, based on the GHQ-12. Of the 260 nurses, only a few (n=8; 3.1%) reported ever being treated for mental health-related issues, with hallucinatory episodes being the chief complaint. They also reported currently being taking anti-psychotic medications.

In addition, when asked: “Have you taken medication on mental health problem in the past”?, only 14 respondents (5.4%) answered “yes” while 18 (6.9%) and 19 (7.3%), respectively, had trouble in controlling violent behaviour and had serious thought of suicide

| Mental health status assessment | Responses (N=260) | Frequency | Percentage |

| Ever hospitalized for mental health issues | No | 252 | 96.9 |

| Yes | 8 | 3.1 | |

| Depression | No | 203 | 78.1 |

| Yes | 57 | 21.9 | |

| Hallucination | No | 252 | 96.9 |

| Yes | 8 | 3.1 | |

| Trouble in understanding | No | 224 | 86.2 |

| Yes | 36 | 13.8 | |

| Trouble in concentrating | No | 199 | 76.5 |

| Yes | 61 | 23.5 | |

| Trouble in remembering | No | 211 | 81.2 |

| Yes | 49 | 18.8 | |

| Trouble in controlling violent behavior | No | 242 | 93.1 |

| Yes | 18 | 6.9 | |

| Serious thought of suicide* | No | 239 | 92.6 |

| Yes | 19 | 7.4 | |

| Presently taking mental health medication? * | No | 250 | 96.9 |

| Yes | 8 | 3.1 | |

| Have taken medications on mental health problem in the past * | No | 244 | 94.6 |

| Yes | 14 | 5.4 |

Missing data: * =2 (N=258)

Table 1: Mental Health Status Assessment of the Nurses

The question “on trouble in concentrating” attracted the most presenting issue (23.5%; n=61), while “trouble in remembering” attracted an 18.8?firmative response (n=49). From the foregoing, many nurses in the study setting currently report some mental health challenges of concern.

As self-reported by the nurses, anxiety and feelings of intellectual incompetency were relatively high: 31.3%) and 41.5%, respectively. As shown in Table 2, other behavioral patterns like cowardly attractive; feeling of worthlessness; feeling of not being loved; hostility; inadequacy, being ugly recorded low scores: 7(2.73%), 7(2.7%), 9(3.5%), 10(3.8%), 6(2.3%) and 4(1.6%) respectively. While guilt feeling was 7.7% (n=20), aggressiveness accounted for 6.9% (n=18) and being misunderstood by people had 13.5% (n=35).

| Behavioural patterns | Responses (N=26) | Frequency | Percentage | |

| In the last one month, I have felt: | ||||

| Worthless | No | 253 | 97.3 | |

| Yes | 7 | 2.7 | ||

| Inadequate | No | 254 | 97.7 | |

| Yes | 6 | 2.3 | ||

| Guilt | No | 240 | 92.3 | |

| Yes | 20 | 7.7 | ||

| Anxious | No | 178 | 68.5 | |

| Yes | 82 | 31.5 | ||

| Aggressive | No | 242 | 93.1 | |

| Yes | 18 | 6.9 | ||

| Lonely | No | 221 | 85.0 | |

| Yes | 38 | 14.6 | ||

| Confused agitated | No | 245 | 94.2 | |

| Yes | 15 | 5.8 | ||

| Ugly | No | 254 | 98.4 | |

| Yes | 4 | 1.6 | ||

| Unloved | No | 251 | 96.5 | |

| Yes | 9 | 3.5 | ||

| Unconfident | No | 235 | 90.4 | |

| Yes | 25 | 9.6 | ||

| Intellectually incompetent | No | 152 | 58.5 | |

| Yes | 108 | 41.5 | ||

| Hostile | No | 250 | 96.2 | |

| Yes | 10 | 3.8 | ||

| Cowardly unattractive | No | 253 | 97.3 | |

| Yes | 7 | 2.7 | ||

| Misunderstood by people | No | 225 | 86.5 | |

| Yes | 35 | 13.5 | ||

| Attractive | No | 144 | 55.4 | |

| Yes | 116 | 44.6 | ||

| Confident | No | 127 | 48.8 | |

| Yes | 133 | 51.2 | ||

| Panicky | No | 237 | 91.2 | |

| Yes | 23 | 8.8 | ||

Table 2: Behavioral Pattern Assessment

Attitude of Nurses towards promotive and preventive mental healthcare (PPMHS)

For the attitude of the nurses towards PPMHS, there are good attitudinal dispositions of the nurses, with a mean values of above 3.0 (positive average: 2.5).

The practice of mental health self-care services among nurses

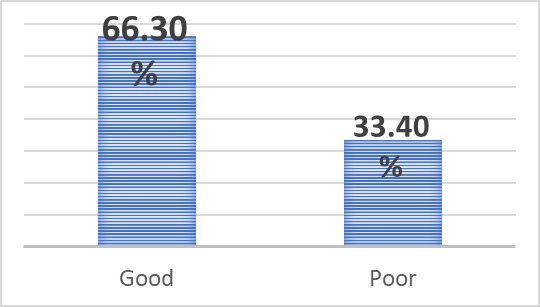

Figure 1 presents level of practice of preventive and promotive mental health care service (PPMHS) among nurses. About two-thirds of the nurses (66.3%; n=173) reported a good level of practice of mental health self-care, with he main methods used by nurses, highlighted in Table 5, namely, stress management techniques (mean: 3.0), engaging in health promotion programmes (mean: 2.9), and counselling (mean: 2.9). Many of the participants also reported the adoption of health education and software approaches (2.8) and mass media channels (2.7).

Figure 1: Proportion of Practice of Mental Health Self-care by Nurses

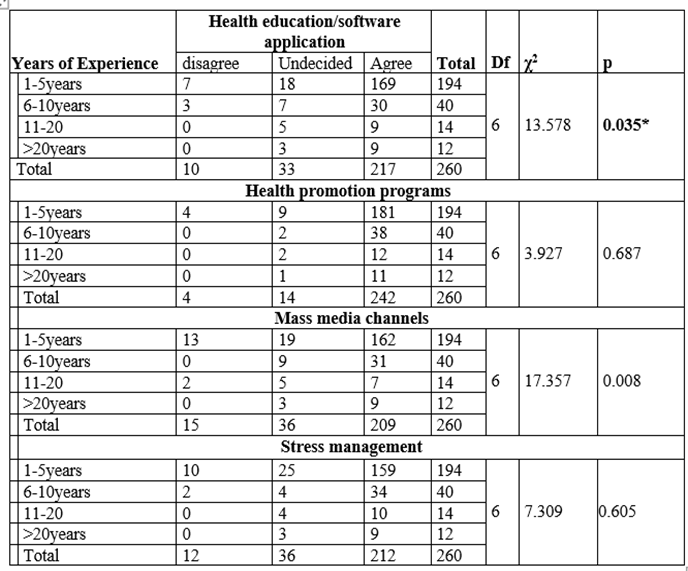

A significant relationship between their years of experience and the methods used showed significant relationships with the use of health education/ software approaches (p≤0.035) and mass media (p≤0.008) (Table 3). Others were not statistically significant. The relationship between the nurses’ attitudes and their practice of promotive and preventive mental health care is shown. The model fitting information (MFI) in the Table is significant (0.000), with the good-of-fit of Pearson and Deviance being 0.60 and 0.870, respectively; and the Nagelkerke value was 0.264 for pseudo R square. Attitude and mental health promotion practices are thus significantly related but attitude did not significantly predict practice.

Table 3: Relationship between Years of Experience and methods used for MHSC

Discussion and Finding

The study examined the mental health status of nurses, as well as their attitude towards and level of practice of promotive mental health self-care. Their socio-demographic characteristics indicate a predominantly young group of nurses with few years of working experience (junior category); the reluctance of the more senior nurses to participate in this study seems to suggest the general pattern of attitude to issues relating to mental health in the environment.

The mental health status of nurses in Ekiti State

Many nurses in this study self-reported some mental health challenges of concern such as “ever being treated for mental health-related issues, with hallucinatory episodes,” with many being on psychotropics. Others reported inability to control aggressive behaviours, battling with suicide thoughts, feelings of worthlessness, not being loved, inadequate, or being ugly, including diminished levels of attention and concentration, and memory lapses. These are mental health concerns. Although these could feature of extreme or severe stress, diagnosable conditions are obvious. In China, Zhang, et al., (2020) in a national cross-sectional survey on mental health status of Chinese healthcare providers revealed nurses who were more anxious, feeling unhappy, and depressed. The few who reported mental health related cases in our present study is way far below the level reported in the national survey for healthcare professionals by Zhang et al., (2020), the mental status of the study participants in this study should attract broader screening to establish a better picture of the issues, as in the Chinese survey.

The attitude of nurses in Ekiti State to mental health self-care

The findings of this study has indicated that positive attitudes of nurses toward practice of promotive mental health care, contrary to findings of previous studies (Al-Awadji, et al., 2017; Hsiao, et al., 2015; Sahile, et al., 2019; Coker, et al., 2018) which had reported nurses’ negative attitude to mental health issues.

Mental Health Self-care Practices of promotive and preventive mental health care

Good practice of promotive mental health care was reported by the nurses in Ekiti State tertiary health facilities, as in Timothy et al., (2017)’s findings in Aro Psychiatric Hospital Abeokuta, in the same setting. In another study Omoniyi, et al., (2016), opinions of 88% of nurses favouring the beneficial practice of mental health promotion and self-care seems to align with their attitude. The years of experience significantly influence the means used for the self-care practices, with software, health education, and mass media options being more influential. The younger cadres of nurses who formed the more of the sample for this study mostly likely explain these preferences: they align more to more strategies of health promotion. However, other nurses’ socio-demographic characteristics are not significantly associated with the practice of promotive mental health care, unlike the findings of Hsaiao, et al., (2015), where the older and experienced nurses showed better level of practice in mental health care. Mental health self-care has been described as self-healing for nurses, irrespective of socio-demographic and perceptual variables. As succinctly put, self-care help to replenish and sustain the energy required to maintain a state of equilibrium (Delgado, et al., 2022; Crane & Ward, 2016), and therefore needs to be given the rightful priority. Self-help strategies should focus the types of self-help strategies, reasons for engaging in self-help activities, and effectiveness of self-help strategies to manage distress (Chang, et al., 2022). More so, as a nursing professional and ethical duty to self (ANA, 2015), self-care translates to quality patient outcomes (Faubion, 2023). It is thus personnel (nursing) and patient care challenge (Cho, 2018). More empirical interrogations on these mental health and emotional components of self-care among nurses are therefore expedient. For example, Moilanen, et al., (2023) has suggested the other means for mental health self-care like the chat box.

Implications for nursing & health policy

Policy: The findings of this study have indicated the low priority on self-care by nurses, further indicating the absence of a clear self-care policy for nurses in Nigeria. This suggests the need for a mental health self-care policy guideline for nurses in particular, and a framework for self-care in general. The regulatory body for nursing and professional associations like National Association of Nigeria Nurses and Midwives (NANNM) and the Association of Psychiatric Nurses of Nigeria (APNON) in Nigeria in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Health like their counterparts elsewhere (e.g. the American Nurses Association) should build this into its ethical code framework for nurses. Policies by these professional associations and the regulatory body of nursing in Nigeria on these are necessary! One suggestion is to enshrine “self-care” in the Nursing and Midwifery of Nigeria (NMCN) Code of Ethics in Nigeria. Thus, self-care will become both an ethical and professional responsibility.

Practice: Many nurses reported many mental health concerns including diagnosable mental disorders. Those who reported mental disorders but not accessing any formal treatment were appropriately referred for assessment and care. Emphasis on mental health screening and self-care management strategies for coping and help-seeking outlets were discussed, especially work-family life balance, to increase capacity for troubles remembering and concentrating which could be due to or triggered by work or other forms of stress. Methods of continuous self-assessment for mental health issues by nurses should be routinely discussed at nursing forums in the hospitals. Periodic evaluation of these findings should also be worthwhile, because mental health self care can help nurses manage stress, lower the risk of illness, and increase energy.

In addition, both nurses and their institutions have to prioritize mental health care, as to the general population. Further actions to encourage more mental health promotion among nurses through available professional channels can be built into existing Mandatory and Continuing Professional Development Programmes (MCPDP) put in place for all Nigeria nurses, in all the States of the Federation. At the individual level, continuous mental health screening and self-care management strategies for nurses are critical.

Further implications of the findings include presenting a seminar on the findings in the Nursing Seminar series of the participating hospitals.

Limitations of the study

The challenges experienced during the study were the reluctance of senior nurses in completing questionnaire despite assurance of confidentiality given during data collection, and the Industrial Disputes at two government-owned institutions at the time of data collection. There was also general apathy of nurses toward participating in research studies in the centre. Nurses who specialize in mental health nursing were quite few in all the institutions; so relating their mental health status and self-care practices between mental health nurses and general nurses could not be determined. However, the researchers ensured sufficient number of data was collected to meet the study objectives. Generalisation of these results to other States in the south-west region of Nigeria and the country was not feasible

Conclusion

This study presents the results of a study on the mental health self-care practices of the nurses working in the three tertiary health facilities in Ekiti State, a southwest State, in Nigeria. While the study identified positive attitudinal dispositions to promotive mental self-health care among the nurses, the practice is low. And this is irrespective of the nurses’ gender and their years of experience. The most common measures adopted by the nurses include various forms of stress management techniques, and participation in health promotion programmes and counselling mainly using software methods. Paucity of funding and unfavorable government policy about mental health research limits constant interrogation of mental health issues among healthcare professionals who are constantly under intense stress. Psycho-education has become inevitable in care settings; mental health education software application on promotive and preventive mental health self-care can be embarked upon. Available mental health nurse in these faculties can be adequately in psycho-education and periodic screening for nurses, and probably other healthcare professionals in the hospitals, using the MHSPMHC tool or other validated scales. Triangulating future studies in more elaborate randomized studies including interventional/ demonstration studies should be revealing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding:

None.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the contributions of various people who have assisted in one way or the other to this work, just to mention; Mrs. O.B. Ajiboye of Federal Teaching Hospital School of Nursing, Ido-Ekiti, Ms Aminat Yusuf of Afe Babalola University Multisystem Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, and our research assistants at all the centres for their individual and collective supports. We also thank the Managements of the hospitals and their Health and Ethics Committees for the approvals and support throughout the period of the study.

References

-

Akinwale, O.E. and George, OJ. (2020). Work environment and job satisfaction among nurses in government tertiary hospitals in Nigeria; Rajagiri Management Journal; 14(1): 71-92; Emerald Publishing Limited -ISSN 0972-9968 e-ISSN 2633-0091; DOI 10.1108/RAMJ 01-2020-0002

--> -

Al-awadhi, A., Atawneh, F. & Zahid, M.A. (2017). Nurses’ attitude towards patients with mental illness in general hospital in Kuwait. Journal of Medical Sciences. 5(1): 31-3

Publisher | Google Scholor -

American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of Ethics for Nurses with interpretive Statements. Maryland: Silver Springs

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Anyebe, E.E., Olisah, V.O., Garba, S.N. and Amedu, M. (2019). The Current Status of Mental Health Services at the Primary Healthcare Level in Northern Nigeria. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research: 1-9:

--> -

Anyebe, E.E., Olisah V.O., Garba S.N., Murtala H.H., Balarabe F. (2020). Availability of mental health services at the primary care level in northern part of Nigeria: Service providers' and users' perspectives. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry; 36(1):157-62.

--> -

Austen, M. (2015). Self-care in Nursing: A Call to Action.

--> -

Barnard, S.A. Alexander, B.A. Lockett, A.K., Lusk, J.J., Singh, S. Bell, K.P. and Harbison, L.A. (2020): Mental Health and Self-Care Practices Among Dental Hygienists. Journal of Dental Hygiene; 94 (4) 22-28

--> -

Bui, M.V., McInnes, E., Ennis, G., and Foster, K. (2023). Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of updated evidence, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Butler, et al., (2019), Six domains of self-care: Attending to the whole person, 29, 107-124.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Chang S, Sambasivam R, Seow E, Tan GC, Lu SH, Assudani H, Chong SA, Subramaniam M, Vaingankar JA. (2021).

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Chipu, M., & Downing, C. (2020). Professional nurses' facilitation of self-care in intensive care units: A concept analysis. International journal of nursing sciences, 7(4), 446–452.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Cho, S. (2018). Nurse staffing and adverse patient outcomes: a systems approach. Nursing Outlook.;49(2):78–85.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Coker, A.O., Coker O.O, Alonge A & Kanmodi K. (2018). Nurses’ knowledge and attitude towards the mentally-ill in Lagos, South-western Nigeria. International journal of advance community medicine. 1(2): 15-21.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Crane, P.J., Ward S.F. (2016). Self-healing and self-care for nurses. AORN J. 2016;104(5):386-400 DOI: 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.09.007.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Delgado, C., Evans, A., Roche, M. and Foster, K. (2022). Mental health nurses’ resilience in the context of emotional labour: An interpretive qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31, 1260–1275.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Faubion, D. (2023). Self-Care for Nurses – 25 Proven Strategies to Take Better Care of Yourself; Your Guide to Nursing and Healthcare Education.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Hsiao, C.Y., Lu H.L & Tsai Y.F. (2015). Factors influencing health nurses’ attitudes toward people with mental illness. International Journal on Mental Health Nursing. 24(3):272-280.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Hosman C, Jané-Llopis, E. Saxena, S. (2016 eds.) Preventing the harm done by substances. In: Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Apter A.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Janine k, (2022). The ultimate guide to self-care for nurses.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Kashyap, G.C. and Singh, S.K. (2017). Reliability and validity of general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) for male tannery workers: a study carried out in Kanpur, India; 17: 102.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Llop-Gironés, A., Vračar, A., Llop-Gironés, G., Benach, J., Angeli-Silva, L., Jaimez, L.et al., (2021). Employment and working conditions of nurses: where and how health inequalities have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic? BMC Human Resources for Health; 19 (1):112.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Mills, J., Wand, T., and Fraser. J.A. (2015). On self-compassion and self-care in nursing: Selfish or essential for compassionate care? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 791– 793.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Moilanen, J., van Berkel, N., Visuri, A., Gadiraju, U., van der Maden, W., Hosio, S. (2023) Supporting mental health self-care discovery through a chatbot. Front Digit Health. Mar 7;5: 1034724. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1034724. PMID: 36960179; PMCID: PMC10028281.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Morgan, O. (2022). Lagos nurses embark on strike over poor working conditions. The Punch. 25.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Murray C.J.L., & Lopez, A.D., (2015, eds): Global Burden of Disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. The Global Burden of Disease and Injury. Harvard School of Public Health.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

O’Malley, M., Happell, B. & O’Mahony, J. (2022) A Phenomenological Understanding of Mental Health Nurses’ Experiences of Self-Care: A Review of the Empirical Literature, Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43:12, 1121-1129.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Omoniyi S.O., Aliyu D., Taiwo A.I., & Ndu A. (2016). Perception of Nigeria mental health nurses toward community mental health nursing practice in Nigeria. World Journal of Preventive Medicine. 4(1):25-33.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Peprah, W.K., Tano, G., Antwi, F.B. Osei, S.A. (2019). Nursing Students Attitude Towards Self-Care Management; Abstract Proceedings International Scholars Conference: 7(1): 18.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Purdue University Global (2023). The importance of self-care for nurses and how to put a plan in place.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Rafael, C. (2014). How to Calculate Sample Size Using Taro Yamane’s Formula.

--> -

Rehm, J., Shield, K.D. (2019). Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep.; 21(2):10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0997 0. PMID: 30729322

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Richards, D.A., Hilli, A., Pentecost, C., Goodwin, V.A., and Frost, J. (2018). Fundamental nursing care: A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of nursing care interventions for nutrition, elimination, mobility and hygiene. J Clin Nurs.; 27: 2179-2188

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Sahile Y., Yitayih, S. & Yeshawnew, B. (2019). Primary health care nurses’ attitudes toward people with severe mental disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health System. 13(26): 34-45

--> -

Sist L, Savadori S, Grandi A, Martoni M, Baiocchi E, Lombardo C, Colombo L. (2022). Self-Care for Nurses and Midwives: Findings from a Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). Dec 7;10(12):2473. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10122473. PMID: 36553999; PMCID: PMC9778446

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Tachias, l.M & Ferguson, R.W (2019). Analyzing self-care initiative of nursing students.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Timothy A., Umokoro O.L, Maron M, Richard G., Ogunwale A., Okewole N., Ogundele A., Olarinde S., Olaitan F., Olopade M & Ogunyomi K. (20170). Experience of trained primary health care workers in mental health service delivery across Ogun State, Nigeria. Clinical Psychiatry. 3:1.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

World Health Organisation [WHO] (2021). Guideline on self-care interventions for health and wellbeing.

Publisher | Google Scholor -

Zing, Y., Tian, L., Li, W., Wen, K., Hongman, W., Gorg, R., Ziyuan, D. & Wu, A. (2020). Mental health status among Chinese healthcare-associated infected control professional during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019: a national cross-sectional survey. Journal of Observational Study. 100(5).

-->